I find it most interesting to read the Brisbane Courier from 100 years ago on a Saturday morning. It brings into stark relief the modern world, that which remains much the same and that which has evolved beyond belief in such a short period of time. Here is a transcription of a recollections of Duncan Laidley who as a 9 year old arrived in Sydney, Australia in January 1842 after a 4-5 month voyage. Below is the text, followed by the scanned copy of the relevant pages and a summary in poetic form generated by AI.

SYDNEY’S EARLY DAYS.

BRISBANE IN 1857.

By C. DUNCAN LAIDLEY.

Born on December 8, 1833, near Brechin, in Forfarshire, Scotland, I am in the shadows of eventide, and ere the break of the new and perfect day I venture to put down some of the recollections of the past, that those who live in these times of ease and plenty may know something of what the pioneers endured in opening up this country.

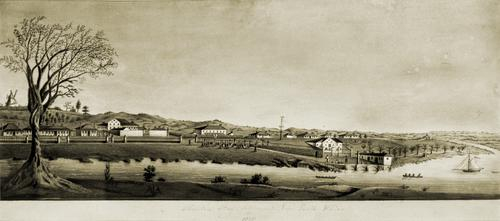

This panorama landscape depicts the Moreton Bay Settlement in 1835. The viewpoint is from South Brisbane, on the site now occupied by the Queensland Cultural Centre. The Brisbane landscape and buildings of the period are depicted. Buildings depicted are the Windmill, with a fence in front and the treadmill building to the left; the row of buildings from left to right are the surgeon’s cottage and convict and military hospitals (three low set buildings in a row); the convict barracks, a multi-storey building with a walled yard; the military barracks, a multi-storey building with a low set guard house just visible to the left; the Engineer’s House, used during Bowerman’s time as offices for the commandant and commissariat staff; the kitchen for, and then the Parsonage building, which by 1835 was being used as quarters for commissariat staff; the Commissariat Stores buildings, with an arched wharf with a crane and sentry box to the front, a small boat house to the left of the wharf, and boat builders hut and storeroom to the right of the wharf; and the Commandant’s House, with a small kitchen/convicts’ quarters building to the left.

The building in the far right of the painting, shown behind a row of trees growing on the river bank, was the Government Gardeners house.

My father and mother, with three sons and two daughters, left Dundee during September, 1841, in the sailing ship, Ann Milne, and landed at Sydney in January, 1842. Our skipper was Captain Thom, and there were about 300 immigrants aboard. We took no cargo, the vessel being fitted up simply as an emigrant ship. It was a regulation in those days that every im-migrant vessel must carry six months supply of provisions and water.

This, for the needs of so great a company, took up all available cargo space for the water was carried in casks between decks. In order to ensure ballast, as the water was used from the casks, sea water was pumped back, thus preventing our load becoming too light as the journey proceeded. We were only a few days in Sydney. The place had in those days no signs of its coming greatness. George street was only a track that led down to what was afterwards Circular Quay. The only deep water was on the west side of Darling Point. There was no landing place for goods east of Millers Point but there was a wharf in Darling Harbour. Immigrants were taken off the ships in small boats, and the ship lay a little off the land .

There was no immigration depot, but persons were allowed to stay on board for a period of one week. If they had not got employment by then, they had to get away and fend for themselves. Nearly every one went about on foot. Horses were very expensive, and all goods traffic was by bullock team. Ten single men from our ship were engaged for station work at the head of the Burnett River, and one of these was Mr Tom Gray, after, of George street Brisbane. They were taken off to a small sailing vessel and brought direct to Moreton Bay.

Thence they went overland, humping their “blueys” guided by a man with a pack horse carrying provisions.

My father was engaged to go to Mr John Eales’s farm on the Lower Hunter River, near Morpeth, as an overseer of convicts. At this time nearly all the labour in the country was provided by the convicts. Owners of land, and some lessees of Crown land, could obtain this labour by applying to the nearest police magistrate and paying the cost of their escort from Sydney. They could get men of almost any trade, including carpenters, blacksmiths, farm hands and shepherds. These men were paid no wages, nor did the Governor receive any consideration for supplying them. Each man received from his employer 10lb. of flour and 10lb of meat per week, and two suits of clothes (not 10 guinea suits, you may be sure) a year. Although not bound to do so by regulation, nearly all these man received, in addition, tea, sugar and tobacco. They were given plenty of work and a bare existence. They were not supposed to go away from the holding of their masters but many were treated leniently, and allowed to go where they would, so long as they turned up for work when wanted. In this manner was Australia’s primary industry originally carried on.

One of the early Governors advised the authorities at home to send out female convicts, believing that when the male prisoners had served their time they would marry them, but the plan would not work. Women convicts were not wanted either by their confreres in crime or by anyone else and I have heard my father remark that he had never met any one who had a good word to say for them.

“IRON” GANGS AND TREADMILLS.

The male convicts were worked often in “iron” gangs and in treadmills. Men were condemned to the iron gang for from one to twelve months. To each leg was rivetted a band of iron about 1 in. by one eighth of an inch, and to this was attached by a chain about 3ft long a solid block of iron weighing 5lb to 6lb. The men were not allowed to lift the iron unless it got entangled in something, they had to drag it with them night and day. No protection from the galling iron was given by the authorities but the men were allowed to tear up an old shirt or garment, and stuff that between the flesh and the iron band and thus protect themselves from its chafing. These men were generally en-gaged in stone breaking. This condemnation followed on very slight offences, such as the striking of an official, for which the punishment might be twelve months in the gang.

The treadmill was a device for milling grain, and was like the paddlewheel of a steamer. The wheel was controlled by a brake, and the speed regulated by letting in more or less grain. There was accommodation for ten or twelve men, who had to keep time or fall down —walking, as it were always uphill but never getting any higher. The punishment was from one to three hours, according to the gravity of the offence. It was thus, the prison grain was ground.

THE OFFICIAL FLOGGER.

Wherever there was a police magistrate there also was an official flogger. No freeman would take this job; it was always a convict who filled this office, and some of these men appeared to be so brutalised by the treatment they had received that they appeared to be almost past feeling. The instrument of torture had a wooden handle about a foot long, and about three-quarters of an inch thick to which was attached some ten thongs of whipcord, about 12 in. long, knotted every two inches. The victim was hung up by the hands to a cross-

beam, his shirt stripped off, and the flogger applied the lash from shoulder to waist. If the flogger was a merciful man, he could be light in his strokes, but, frequently he was a callous brute, and when he brought the flail down would give it a sharp pull towards himself and thus break the skin at every stroke For trivial offences, such as insulting behaviour to those over them, men were condemned to from 25 to 100 lashes. I have heard my father say that he never knew of one sent to a police magistrate who did not receive a flogging. The poor convicts had no one to plead their case, no witnesses were called; it seemed to be taken for granted that they were guilty. Such was “British justice” in those days and when we com-pare these things with the modern treatment of criminals-skilled counsel freely given and picture shows in gaol–we may reflect how far we have travelled in the science of penology.

EARLY SETTLERS

In 1844 the convicts let out for labour were called in, as it was termed. The farmers who had employed them did not fill their places with free labour because the price of produce had fallen so low that they could not afford to pay wages.

Thus their cleared land was allowed to grow weeds. By degrees, however, it was taken up by men with families in blocks of from 20 to 30 acres, under a grain rent of from three to five bushels of wheat per acre. Wheat was then usually 2/6 a bushel. As the land owners had lots of working bullocks and implements they sold them to their tenants on time payment. Although these early settlers did not get rich, they made comfortable homes, and keeping one or two cows, fowls, etc, they generally managed to rub along all right.

Stock owners had to employ free labour, because all sheep had to be looked after during the day and put in hurdles at night. By 1843 stock were so plentiful that there was no demand for one half of them as meat. To relieve this situation boiling down works were started on the Lower Hunter River, but this failed to cope with the surplus. I have seen thousands of tons of the finest meat that could be produced in any part of the world carted out to rot. The fat and hides only were exported, and anyone going to the boiling down works could get a hindquarter of beef or mutton at a penny a pound. This was continued for quite a number of years in fact, prices remained much the same until after gold was dis-covered in New South Wales, and, later in Victoria when people from all parts of the world came here in thousands.

THE ABORIGINALS

Aboriginals were very numerous when we came to the Hunter River in 1842. I have seen as many as 500 in one camp at a corroboree, with more than a score of half castes. In less than 40 years nearly all had disappeared-half castes and all. I have asked several old colonists if they could account for their disappearance, but I have never had a satisfactory answer. The blacks were very useful to the early settlers. They were often employed in husking corn (maize). Husking and threshing machines were not known in those days. The first sheller I saw was brought by the master of a timber-laden vessel from America in 1852. There was no saw milling machinery. Up to that time all timber was sawn by hand over a pit. One man stood on the log and directed the saw and the other in the pit below. All nails were made by hand. Common sayings were: “As busy as a nailer,” and “He has too many irons in the fire .” Each man would have from three to five rods in the fire at the same time, and he took them out by turns.

About two or three years before we came to Australia a company had been formed in Sydney, known as the Hunter River Steam Navigation Co, for the purpose of running steamers between Sydney and Morpeth, the head of the navigable waters of the Hunter River. This company had two steamers built in Scotland and, after their trial trip, their paddles were taken off and stowed on board, and the vessels came out under sail, because they could not carry sufficient coal to bring them even halfway. There was no lighthouse at Newcastle, so the steamers left Sydney in time to reach there by daylight. There they took in coal. It was brought in drays and tipped on to the wharf, and then taken on board in wheel barrows.

GOLD SEEKING AND FARMING.

In 1852 I went to the gold diggings about 20 or 30 miles south of Mudgee. I spent about a year there, but as I found that I was not getting any richer I returned. I then started farming on my own and married . In 1854 I went for a trip to Sydney. As we were nearing Sydney Heads we saw what none on board had ever seen before— a steamer without paddle wheels. Our captain signalled her, and got the reply: “Cleopatra, from San-Francisco.” A few days later I went to Parramatta by rail-the first railway in Australia-and whilst there I was shown the tree against which Lady Mary Fitzroy was killed by the bolting of her carriage horses.

During the early part of 1857 I came to Brisbane with the intention of making a home here . I bought land at Bald Hills, on the South Pine River, adjoining land bought by my brother and brother-in-law (John Stewart), a short time previously. Towards the end of that year we all came to Moreton Bay in the steamer Yarra Yarra (Captain Bell). We landed at South Brisbane, where the A.S.N. Co. had a wharf. We each brought with us two draught horses, a dray and some farming implements. On the day of our arrival we went out to Bald Hills, and were the only settlers there for some time. Our nearest neighbours were at German Station (Nundah).

There were no houses at Sandgate at that time, and some time later the first house was built by a man named John Louden. As the aboriginals were very numerous, and not to be trusted, the New South Wales Government in 1858 established a black police camp near Sandgate, with six black troopers and a white man, Lou Wheeler, in charge. This camp remained for six or seven years, and it was then removed further north. In those days the Yarra carried mail from Sydney and made the trip once a fortnight. Mail bags (letters only) were taken by pack horse, direct from the steamer to Ipswich and newspapers and parcels were sent by boat travelling with the tides.

All heavy goods were taken in punts, some of which were very large. Edmund Mellor and a mate owned one of these punts, and did very well. Afterwards they bought the Bremer, and later the much talked of Settler was bought by Mr. Mellor. He also had a small steamer built by Smellie and Co., and named it after his wife (my sister). About 1859 the A.S.N. Co., finding that it had not sufficient room at its wharf in South Brisbane, offered to buy the land on each side of its property, but the owners asked such a high price—evidently thinking the company would be compelled to buy— that the sale was not made. Instead the company bought land on the North Side where its present wharves are situated. From that day the North Side progressed faster than the

South. In this same year Cobb and Co started to run coaches to Ipswich, and they continued to do so until the railway was completed to Roma-street.

A Pioneer’s Recollection

Born in Scotland’s rugged land, in the year of ’33,

I sailed to distant shores, a land that promised to be free.

On December 8, my journey began, a child of destiny,

Near Brechin’s ancient stones, my path was set, you see.

With family in tow, we embarked on the Ann Milne,

A vessel fit for emigrants, with provisions, it did gleam.

Three hundred souls aboard, on a boundless, hopeful dream,

To Sydney’s distant shore, we sailed, under heaven’s gleam.

Sydney’s shores we reached in early ’42, a land unknown,

George Street a mere track, Circular Quay’s fate yet to be shown.

No signs of future grandeur, in those days it was not known,

We immigrants disembarked, far from what has since grown.

Immigrants, we wandered, with no depot to our name,

A week to seek employment, or leave, that was our claim.

Bullock teams and footprints, on the roads we came,

In this new land, our destiny, no two lives the same.

My father to the Hunter, as an overseer, was led,

Convicts were the workforce, and landowners well-fed.

From carpenters to shepherds, they toiled until they bled,

A colony built on their sweat, where pioneers had tread.

Iron gangs and treadmills, a harsh and cruel fate,

For petty crimes, they suffered, under a heavy weight.

Chains upon their ankles, dragging stones, their state,

Their plight, a harsh reminder, of a time we now debate.

Official floggers, calloused hands, with whipcord as their tool,

Brutality and pain inflicted, on bodies far from cruel.

No plea for justice, no mercy as a rule,

A time when “British justice” meant torment as a school.

In ’44, convicts’ labor ceased, as farmers faced despair,

Land left uncultivated, free labor was not there to bear.

New settlers took the reins, with courage and with care,

Australia’s pioneers, a future they’d declare.

Sheep in numbers uncounted, as meat supply outpaced,

Boiling down works emerged, the surplus had to be displaced.

Fine meat, left to rot, such waste, it was disgraced,

The fat and hides exported, in that era misplaced.

Aboriginals in tribes, a culture old and grand,

In ’42, I saw them, a presence in the land.

500 at a corroboree, they danced upon the sand,

But in 40 years, most were gone, like castles in the sand.

They worked among the settlers, husking corn with care,

No machines to ease their toil, just hands and sunlit air.

Nails forged by convict hands, in fires with a fiery glare,

A time of sweat and labor, their hardships hard to bear.

Steamers sailed from Scotland, without paddle wheels to see,

Steam power made its entrance, upon the endless sea.

A railroad’s first appearance, a wondrous sight to be,

Australia’s modern era, it opened history’s key.

In ’52, I sought for gold, with dreams of wealth untold,

But fortune wasn’t with me, my story to be told.

Back to farming, I turned, my future to unfold,

In ’54, Sydney’s Cleopatra, her history did unfold.

In ’57, to Brisbane, with a vision to create,

Land at Bald Hills, a new life to initiate.

With horses and a dray, and tools to cultivate,

A settlement begun, where pioneers met fate.

Aboriginals of that time, in distrust they dwelled,

A black police camp established, to help their fears dispelled.

Aboriginal troopers, with courage, they were shelled,

A changing world around them, as pioneers unveiled.

The Yarra carried mail, a fortnight’s time to wane,

Pack horses brought letters, news sent across the plain.

Heavy goods by punts, transported in the rain,

The era’s challenges and triumphs, history does retain.

Edmund Mellor and his mate, with punts, they took the lead,

The Settler and the Bremer, their legacy to heed.

The North Side’s progress, where fertile lands recede,

In ’59, the A.S.N. Co. found its new seed.

Cobb and Co. on coaches, to Ipswich they would ride,

Until the railroad’s advent, where tracks would coincide.

A new era had begun, with progress as our guide,

The pioneers of olden days, their tales, in us, reside.