This paper in the latest edition of Economic Geology by Ágnes Takács, Ferenc Molnár, Judit Turi, Aberra Mogessie,

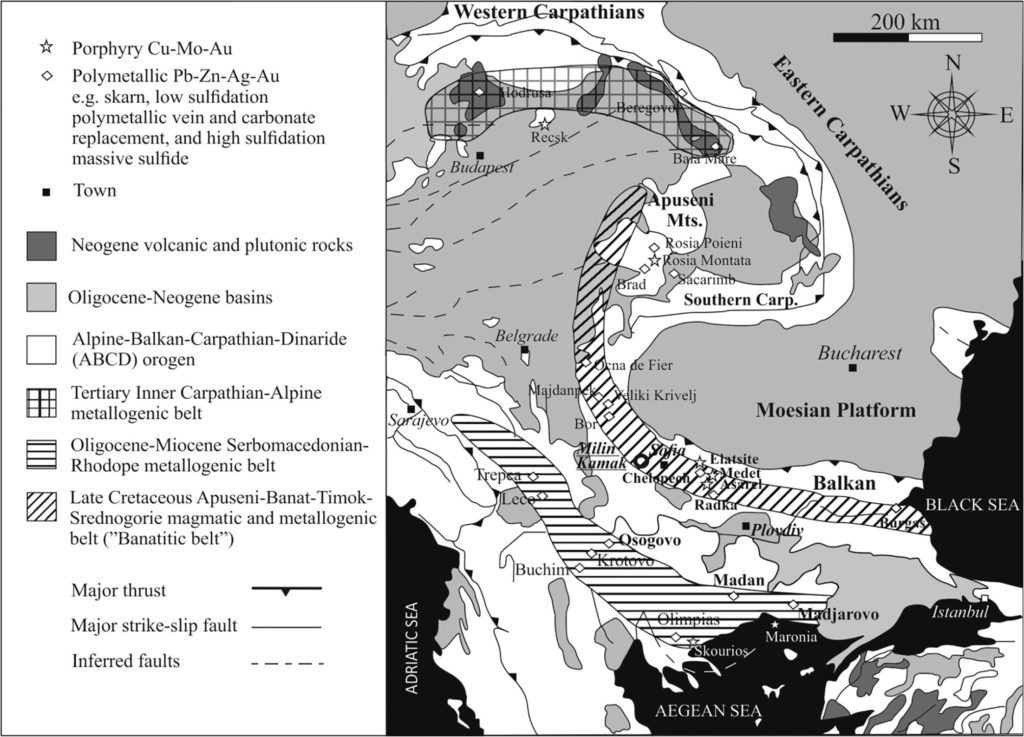

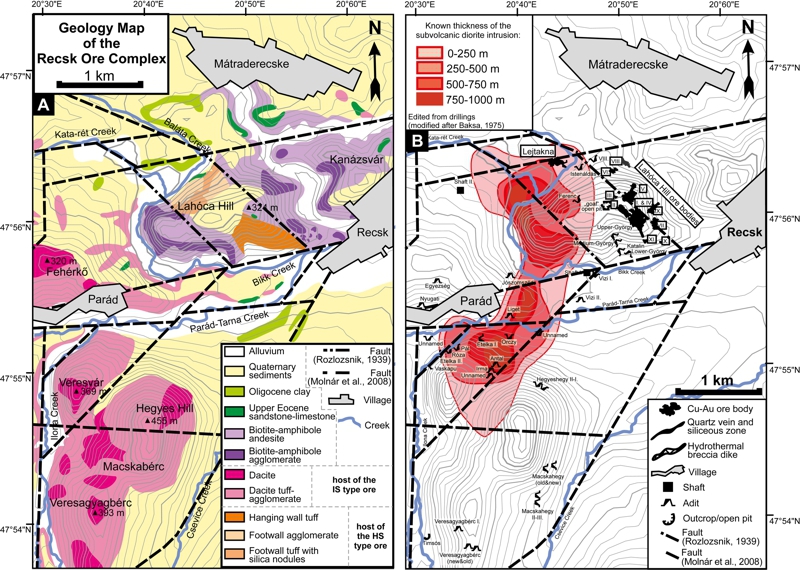

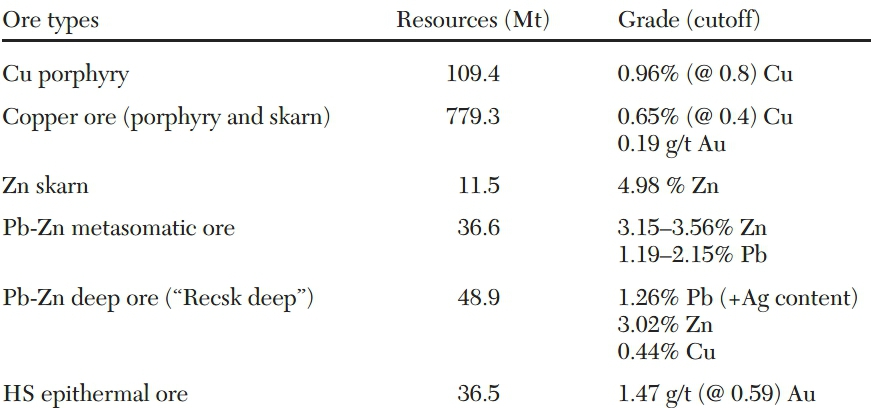

John C. Menzies examines the evolution of the outcropping epithermal mineralisation at Recsk in Hungary. The epithermal deposit sits close to the apex of a large intrusive body which does not outcrop but was defined by systematic diamond drilling to 1,200 metres over a 35km2 area. While the outcropping HS epithermal mineralisation was sporadically mined, the unexposed porphyry and related skarns and replacement bodies was not exploited. The deeper mineralisation has been evaluated with 156,000 metres of drilling from surface and 90,000 metres of diamond drilling from underground development on two levels accessible via two 1200 metre deep, 8 metre internal diameter concrete lined shafts. There is considerable potential for the discovery of both additional mineralised bodies (this paper suggests an as yet undiscovered intrusive to the north of the known body) and extensive skarn mineralisation around the periphery of the intrusion.

HIGHLIGHTS

- Largely uneroded porphyry-skarn-epithermal metallogenic system of Paleogene age in a subduction-related magmatic hydrothermal environment within the Alpine-Carpathian region

- Paleogene diorite intrusions and Mesozoic carbonate and silicic shale host rocks contain Cu(-Mo-Au)-porphyry, Cu-Zn(-Fe) skarn, and metasomatic Pb-Zn (carbonate replacement) mineralization from ~400- to at least 1,200-m depth below the surface.

- Three stages of ore formation

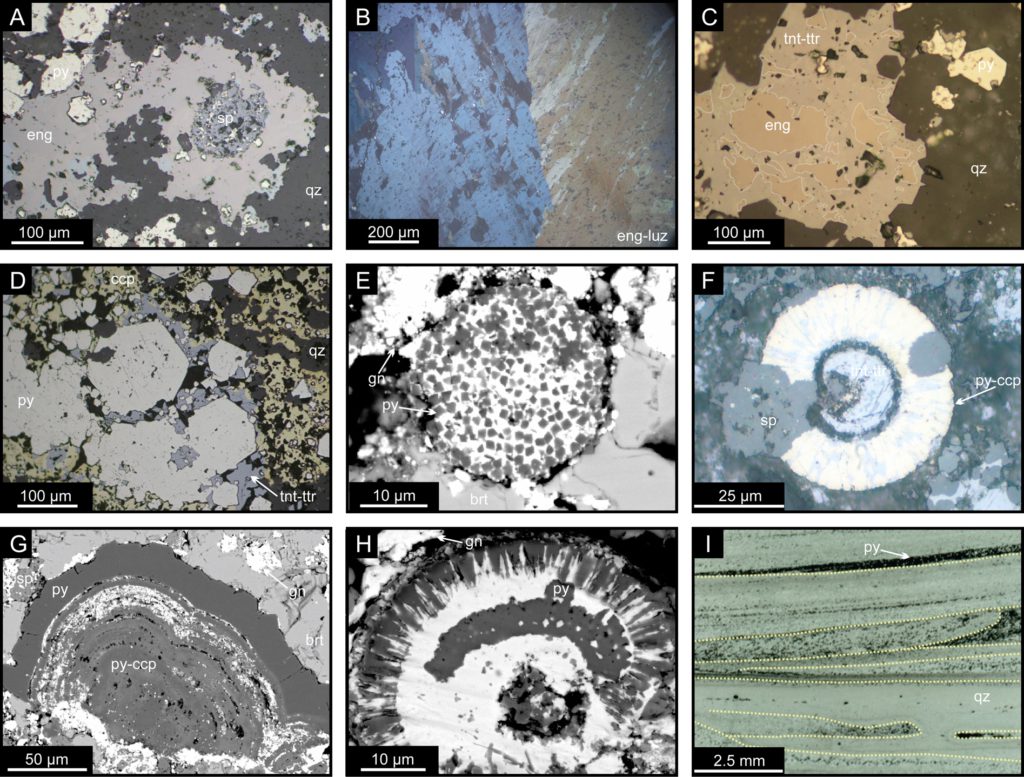

- Stage 1: Ore deposition in the porphyry-epithermal transition zone (pyrite, chalcopyrite, tennantite-tetrahedrite, galena, sphalerite; 260°–230°C; logfs2~–11 to –9; logfTe2~ –19 to –14)

- Stage 2: High- and very high sulfidation state mineralization from tellurium-saturated fluids (e.g., enargite, luzonite, pyrite, native gold, calaverite, hessite, aikinite-bismuthinite; 240°–170°C; logfS2~–7 to –11; logfTe2~–14.8 to –10.5)

- Stage 3: Late-stage mineralization from tellurium-oversaturated, locally oxidized fluids of an intermediate-sulfidation state (e.g., tennantite-goldfieldite, pyrite, hessite, petzite, native tellurium, kawa-zulite; logfs2~–11 to –15.5; logfTe2 ≥ –10.5)

ABSTRACT

The Recsk ore complex is an example of a largely uneroded porphyry-skarn-epithermal metallogenic system in a subduction-related magmatic hydrothermal environment within the Alpine-Carpathian region. Paleogene diorite intrusions and Mesozoic carbonate and silicic shale host rocks contain Cu(-Mo-Au)-porphyry, Cu-Zn(-Fe) skarn, and metasomatic Pb-Zn (carbonate replacement) mineralization from ~400- to at least 1,200-m depth below the surface. The Mesozoic sedimentary rocks are unconformably overlain by a stratovolcanic sequence of andesitic to dacitic composition that hosts epithermal Cu-Au-Ag and Au-Ag-Pb-Zn mineralization. This study focuses on the shallow high-sulfidation epithermal Cu-Au-Ag mineralization exposed and exploited on Lahóca Hill. The ore mineralogy combined with the microthermometry of quartz- and enargite-hosted fluid inclusions suggest three stages of the ore formation: (1) early-stage ore deposition in the porphyry-epithermal transition zone (pyrite, chalcopyrite, tennantite-tetrahedrite, galena, sphalerite; 260°–230°C; logfs2~–11 to –9; logfTe2~ –19 to –14); (2) high- and very high sulfidation state mineralization from tellurium-saturated fluids (e.g., enargite, luzonite, pyrite, native gold, calaverite, hessite, aikinite-bismuthinite; 240°–170°C; logfS2~–7 to –11; logfTe2~–14.8 to –10.5); and (3) late-stage mineralization from tellurium-oversaturated, locally oxidized fluids of an intermediate-sulfidation state (e.g., tennantite-goldfieldite, pyrite, hessite, petzite, native tellurium, kawa-zulite; logfs2~–11 to –15.5; logfTe2 ≥ –10.5). The observed differences in ore mineral assemblages and trace element compositions of sulfides reflect the temporal and spatial evolution of the ore-forming hydrothermal system. Results of fluid inclusion microthermometry performed by conventional and infrared-light microscopy and Raman spectroscopic studies support a model with lateral flow of shallow hydrothermal fluids. The spatial distribution of paleotemperature data within the high-sulfidation portion of the ore deposit suggests that the fluid flow system is offset from the closest apex of the related mineralized porphyry stock. This could be due to structural complexity related to syn- to postmineralization tectonism and/or due to the presence of an undiscovered intrusion to the north of the known mineralized stock.

Original Research here