In early writing, words were not separated by spaces, a format known as scriptura continua. Scribes wrote without breaks between words, reflecting the way language was originally spoken. Just as we don’t pause between every word when we speak, early writers didn’t think to insert spaces between words when writing. They were simply transcribing what they heard, with no established rules for word separation or word order. Similarly, young children today often write words together when they begin to write, following a natural inclination to mimic speech.

In ancient times, word order wasn’t crucial for conveying meaning, since spoken language relied heavily on inflection and emphasis. This oral tradition carried over into writing, so the placement of words in a sentence wasn’t as important as how they sounded when spoken. As a result, early readers could not rely on word order to understand a sentence’s meaning.

The absence of spaces and word order conventions made reading extremely challenging. According to historian John Saenger, in his book Space between Words, ancient readers had to work hard to interpret texts. Their eyes moved slowly, often backtracking to decipher where one word ended and another began. Reading was like solving a puzzle, engaging the brain’s problem-solving and decision-making regions. The cognitive effort required was intense, making reading a slow and laborious task.

Since reading was so difficult, almost no one read silently. Sounding out the words was crucial for understanding the text, as it helped break the flow of continuous syllables. Despite what seems like a cumbersome process today, the lack of spaces between words didn’t pose a significant issue in ancient cultures still deeply rooted in oral traditions. Readers often enjoyed the rhythmic patterns and sounds of spoken language, so the absence of word breaks in Greek and Latin was not seen as a major obstacle. Additionally, many literate Greeks and Romans preferred to have their books read aloud by slaves, further reducing the need for individual silent reading.

In essence, early reading practices were shaped by the oral traditions of language, and the complexities of written text were accepted as part of the reading experience. We are now embarking on a technological transformation in what we read and the way we read it. This is reshaping our brains and the result is increasingly an inability to focus and for many the near impossibility of reading the printed word in anything but the shortest form-factor.

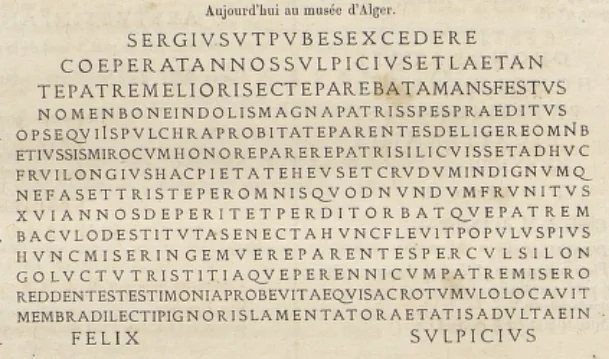

A translation of the above courtesy of a Reddit user.

Sergius Sulpicius, as he had began to leave childhood, as he was setting upon a better path to the happiness of his father, loving, happy, good natured, a great hope to his country, obedient, honest, who respected his parents and everyone else. And he would have obeyed his father with marvelous honor had he been allowed to enjoy this piety any longer. Alas! What a cruel and unworthy crime, sad for all. For as he was not yet 16 he died and deprived his father of his support in his poor old age. The pious people grieved him. His family cried for him, afflicted by a long grief and an eternal sadness, and with his father gave proof of his just life, and placed the body of his loved son in a sacred tomb, he who grieved for his adult life, the unhappy Sulpicius