Authors Pearl Connelly & Lynley Wallis

Purchase: Mitakoodi Traditional Medicinal Plant Uses of the Cloncurry Region can be purchased on-line

Most photos are the copyright of Pearly Connelly & Lynley Wallis

The country around Cloncurry comprises the traditional lands of the Mitakoodi People. In this book, Mitakoodi Elder Pearl Connelly teams up with archaeologist Lynley Wallis to provide an overview of the local plants that are used to treat a range of ailments and illnesses. Drawing on available botanical, ethnohistorical and ethnographic accounts, and exploring how other Aboriginal groups also use these same plants, this book provides an excellent introduction to medicinal plant uses in the local region.

Kar Kar details more than 30 native plants that are still used by Aboriginal peoples in Australia and the following is a summary of the introduction and a couple of examples of specific species. If you are heading into the Cloncurry region then get a copy of this wonderful book.

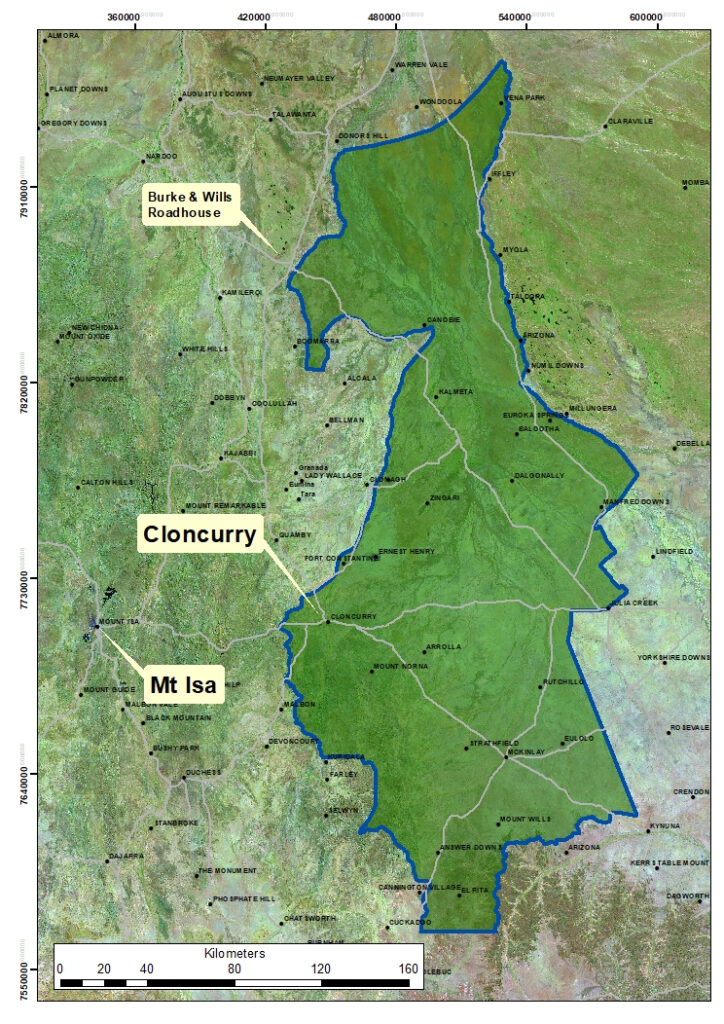

Mitakoodi Country

Mitakoodi country centers around Cloncurry in northwest Queensland, Australia. The region experiences a tropical northern savannah climate with distinct wet and dry seasons. Cloncurry Airport data reveals average daily lows between 10-25°C (warmest from October to April), and average highs between 26-39°C (coolest from May to August). The area receives about 540 mm of rain annually, mostly concentrated between December and March. Edward Palmer, who documented Aboriginal groups in the Cloncurry region starting in 1864, described the Mitakoodi (who he called the Mythuggadi) territory as a hundred square miles encompassing the Upper Cloncurry River, Julia Creek, McGillivray’s Station on Eastern Creek, and part of the Flinders River across the immense treeless downs.

The Gulf Plains bioregion, characterized by vast black soil plains and open woodlands and grasslands, largely defines the Mitakoodi country. Mitchell grasses are the dominant species in these grasslands. Eucalyptus species are commonly found in the open woodlands. Further south, the landscape transitions to sandstone and basalt areas, where turpentine and spinifex thrive. Numerous small watercourses, particularly in the south, support various Eucalyptus and Melaleuca species.

Aboriginal Uses of Plants

Kar Kar explores the significance of plants in Aboriginal society, particularly their medicinal uses.

- Plants played a crucial role in Aboriginal society, extending beyond their dietary importance. They were used for various purposes, including:

- Crafting artifacts such as shields, coolamons, digging sticks, boomerangs, and spears.

- Constructing shelters, ranging from simple windbreaks to complex structures.

- Providing raw materials like seeds, strings, and adhesives for making nets, baskets, and adornments.

- Serving as a vital source of medicine for healing injuries, treating illnesses, and preventing diseases.

Plants played a crucial role in Aboriginal society, extending beyond their dietary importance. They were used for various purposes,

The arrival of Europeans brought about significant changes in how Aboriginal people interacted with plants. Factors such as altered firing regimes, limited access to traditional lands, and the introduction of new animal species impacted the distribution of native Australian vegetation.

Despite these changes, Aboriginal communities retain valuable knowledge about plant use, particularly in medicine. Recent collaborative projects aim to document this information for future generations.

Kar Kar highlights several consistent themes in Aboriginal medicinal plant use:

- Broad-spectrum use: A single plant species might have multiple uses. This strategy was practical for nomadic lifestyles.

- Knowledge of plant components: Different parts of a plant, such as leaves, roots, barks, flowers, and stems, may have distinct uses and potencies.

- Symptom-based treatment: Treatments typically address the symptoms of an illness rather than focusing on specific diseases.

- Preventative medicine: While less common, preventative medicine exists, particularly in practices like smoke therapy for infants, believed to promote strength and ward off future illnesses.

Kar Kar draws parallels between traditional Aboriginal methods and contemporary Western medicine in preparing medicinal extracts from plants. Both employ methods like infusion, decoction, direct crushing, maceration, and emollient preparation.

Kar Kar provides insights into these preparation methods:

- Infusion involves steeping plant material in hot (but not boiling) water.

- Decoction uses boiling water to break down tougher plant materials like bark and roots.

- Maceration is a gentler process of soaking plant material in cold water to release active compounds.

- Emollient preparation involves crushing or burning plant material and mixing it with animal fat, often from a goanna, to create an ointment for topical application.

The most prevalent traditional methods are crushing, maceration, and emollient preparation, often used for external applications like body washes or ointments.

Indigenous medicines are usually prepared fresh to maintain their efficacy. However, medicines prepared with goanna fat can be stored for extended periods, ideally in metal containers.

A Note of Warning

Many of the plants documented in this book could well be toxic and have to be carefully prepared and administered. If you are determined to try some of these medicines then they should be treated like any pharmaceuticals, you should see expert advice and that expert advice in with the Mitakoodi, in Cloncurry!

Bush Medicine

The following are three examples from Kar-Kar that highlight the diversity of the content from edibles to broad spectrum medicinals, natural soap, mosquito and hunting aides.

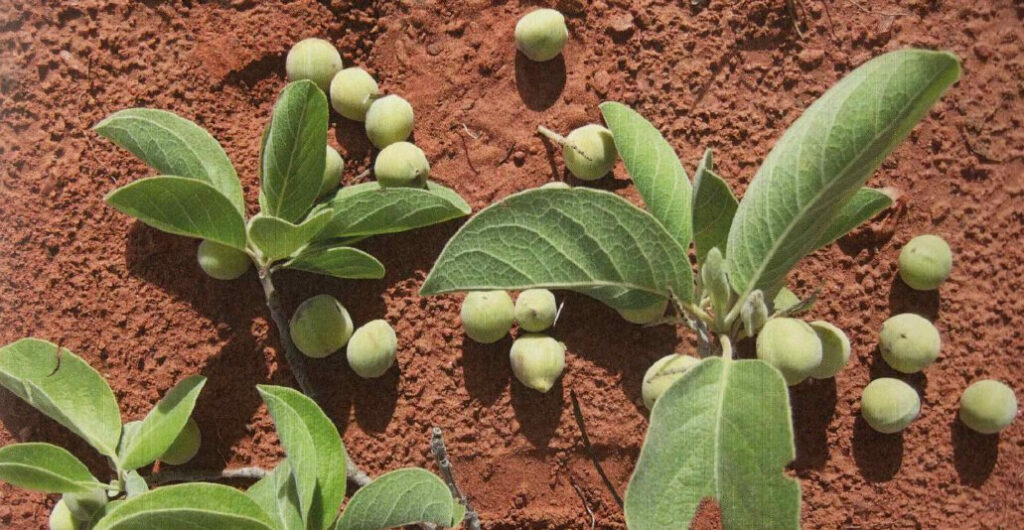

Bush Apricot/Arid Peach

The bush apricot, or arid peach, is a deciduous tree that grows up to 10 m in height. The leaves are oval shaped, furry, and can be up to 14 cm long and 9 cm wide, though there is a lot of variation in size. The leaves are clustered at the ends of branches in a distinctive pattern with pale undersides and prominent veins.

The small, cream-colored flowers grow on small spikes. The mature fruit is round and turns brownish orange as it ripens. The fruit is similar to a miniature apricot in appearance and flavor. The fruit can be dried and rehydrated with water. In Mitakoodi country, the bush apricot grows on rocky hill slopes and is recognizable for its bright green foliage. The Mitakoodi people eat the bush apricot fruit. They also use the plant medicinally to treat stomach aches and other pains.

Conkerberry

The Conkerberry plant is a sprawling, thorny shrub that grows up to 3 meters tall. Its leaves are lime green, narrow, leathery, and have a unique opposite arrangement where a small spine grows at the base of each leaf. The plant produces small, white, fragrant, star-shaped flowers with five petals that bloom after rainfall. Conkerberry plants thrive in sandy soils and can be found in open shrubland or on gravelly rises. The plant proliferates in large quantities on pebbly ridges along the Cloncurry after the wet season, specifically after February.

The fruit, or Conkerberry, develops from a green to a dark purple-black color when ripe, resembling an oblong shape. Each berry measures less than 1 cm long and serves as a good source of vitamin C. The fruit has a short lifespan on the plant, often falling to the ground or being consumed by birds.

Beyond its nutritional value, the conkerberry plant holds medicinal significance. The roots are particularly potent and provide an effective treatment for sores. The Mitakoodi people utilize the roots in a unique boiling process: they boil the roots in water, drink the resulting liquid, and then use the boiled roots as a poultice for aches and pains. This liquid is also used as an eyewash, a practice also found among the Yindijibarndi people. Infusions made from the roots can be used for bathing sores.

The Mitakoodi people also consume the fruit. All parts of the plant can be processed into an oily sap used as a liniment for rheumatism. The leaves of the plant are burned as a mosquito repellent or to provide strength for journeys. The plant’s sap is reported to treat rheumatism and in Central Australia, the thorns, rather than the sap, are used to treat warts.

Soap Wattle

Soap Wattle is a large shrub, sometimes a small tree, which grows up to 5 meters tall and is often found along the edges of seasonal creek lines. It has straight, broad leaves that are grey green to silver in color and can grow up to 25 cm long.

The leaves have two or three prominent veins. When they are young, the leaves are covered in fine, silky hairs, though older leaves sometimes lose these hairs. The soap wattle has dense yellow flowers that occur in pairs or singularly in the upper leaf axils. Flowering occurs in winter. The seed pods, which are bright green and 2-5 cm in length, are tightly coiled and grow in tangled clusters. As the pods age, they become brown and brittle.

The Mitakoodi people used the soap wattle’s seed pods for several purposes. One of the main uses was as soap: the pods were rubbed in the hands with water to create a foam. This foam is also an effective mosquito repellent.

Traditionally, the Mitakoodi people also used the soap wattle as a fish poison. They would break or cut branches off the plant and place them in a waterhole. The water in the waterhole had to be still, rather than running, so the toxins would have time to work and stun the fish. The stunned fish would float to the surface where they could be easily collected. While the entire branch was placed in the water, the seed pods contain the stunning poison. The poison is most potent when the seed pods are still young and green. Older, dried pods can be used, but they are not as potent. It is important to note that people cannot drink the water after it has been poisoned with soap wattle. They must wait until the next rains or wet season to flush out the toxins. This method could also be used to hunt emus. When they drink from the affected water, they become “drunk” and are easily caught.

The tannins in the bark and the saponins in the pods are most likely responsible for stunning the fish. Tannins are not as potent as saponins when it comes to fish poisons and are usually slower to act. Saponins are highly effective and can be effective within 30 minutes.

Among other Aboriginal groups, an infusion of the bark has been used to treat laryngitis, while the bark, leaves and pods are used to treat skin itches, infections and headaches, presumably by preparing a decoction.

About the Authors

Pearl Connelly, a Mitakoodi woman, was born in Cloncurry in 1945. The document discusses Connelly’s childhood, family, and the motivation behind her book about bush medicine. Connelly grew up in an Aboriginal reserve near Cloncurry. Her father, Ted, was a Mitakoodi man who worked various jobs, often involving the bush. Her mother, Joyce, was of Waanyi and Chinese heritage. Although the family experienced financial hardship, they were rich in family and culture. Connelly emphasizes the importance of the bush in her life and her family’s history. She learned about traditional Mitakoodi culture, including bush tucker and survival skills, from her extended family, particularly her grandmothers. The document emphasizes the significance of passing this knowledge down through generations. Connelly’s family would hunt for bush turkeys and pigeons for sustenance. Connelly’s younger sister, Margaret, published a book about bush tucker in 2006, which is widely used in the region. Connelly’s book aims to pass on her knowledge of bush medicine to future generations of both Mitakoodi and non-Mitakoodi people.

Lynley Wallis Professor Lynley Wallis is the Principal Archaeologist at WHC, with over 20 years of experience in archaeological research and cultural heritage management across various Australian states and internationally in Thailand and Chile. She has held academic roles at several universities and served as a Senior Heritage Officer with the ACT Government. Currently, she advises the Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation and teaches at Griffith University. Lynley is known for her commitment to community engagement and collaborative projects, having led significant research initiatives funded by the Australian Research Council. Her contributions have earned recognition, including a nomination for the Best Collaboration at the Northern Territory Natural Resource Management Awards. She is a published author in national and international journals and serves on editorial boards, demonstrating her expertise in archaeology and cultural heritage management.

Purchase: Kar-Kar can be purchased on-line

Further Reading

Bindon, P. 1996 Useful Bush Plants. Perth: Western Australian Museum.

Isaacs, J. 1987 Bush Foods: Aboriginal Food and Herbal Medicine. Sydney: Lansdowne Publishing.

Lassak, E.V. and TMcCarthy 1997 Australian Medicinal Plants. Kew: Reeds Books Australia.

Milson, J. 2000 Pasture Plants of North-West Queensland. Brisbane: Department of Primary Industries.

Moore, P. 2005 A Guide to Plants of inland Australia. Sydney: Reed New Holland.

Webb, L. 1959 The use of plant medicines and poisons by Australian Aboriginals. Mankind 7(2):137-146